Vietnamese Overseas After 50 Years (1975-2025)

(Part 2)

Fig. 1: Eden Center in Falls Church, Virginia

This is where local Vietnamese, as well as those from elsewhere, come to shop, share a meal and meet for traditional festivals such as Tet or the Mid-Autumn Festival, as well as to commemorate important historical days such as April 30.

Socio-political Context in the US:

Vietnamese immigration to the United States before 1975 was negligible. In the 1950s, the population of Vietnamese immigrants living in the United States was only in the low hundreds. These immigrants were typically students, war brides of American servicemen, or highly skilled professionals such as doctors in training. This population did not significantly increase until near the end of the Vietnam War, with a sudden surge in the 1970s. The American involvement in the Vietnam War was also a period of confusion and division for the American people.

At that time, for many of us who had just arrived in the U.S. from refugee camps, it felt like being in heaven. Our primary sentiment was gratitude towards this country for sheltering us and providing us with a life of freedom and prosperity.

However, conflicts did occur, such as in the case of refugees in Alamo Bay, Texas, who faced significant challenges:

● Economic competition: They threatened the livelihoods of local shrimpers in the fishing industry.

● Cultural conflict: Their integration into a predominantly white community led to misunderstandings and cultural clashes, further complicating their settlement process.

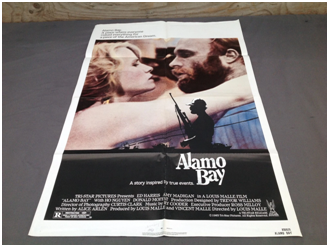

In 1984, the film Alamo Bay, directed by Louis Malle (French), addressed the conflict from four years prior. The role of the struggling young man named Dinh, who fought against the discriminatory American veteran, was played by a Vietnamese-born DNA researcher who transitioned into acting. The director faced a huge problem finding suitable actors, even inexperienced ones, so he advertised for actors in various newspapers and on radio stations in several American cities. Despite having no acting experience, Ho Nguyen auditioned and impressed the casting directors and Malle himself. Ho Nguyen's film career turned out to be very brief.

Fig.2: Alamo Bay movie house poster: “Alamo Bay: A place where everyone risks everything for a piece of the American Dream”

Fortunately, the film was quite favorable to the image of Vietnamese people. It challenged negative stereotypes about Vietnamese refugees, portraying them as hardworking individuals striving for the American Dream, rather than passive victims or a threat to Americans. But in the end, "In the long run, the Vietnamese not only continued to cling to the sea but also thrived.” “We like the weather here, we like shrimping, we like the opportunity to start our own businesses,” one told The Washington Post in 1984. The newspaper called it “the classic American immigrant story. They came, they worked hard, they sacrificed, they overcame hostility and violence, they won”.

After the Vietnam War, two different waves of immigrants arrived in the United States. The first wave occurred after the fall of Saigon in April 1975, with 125,000 Vietnamese refugees fleeing to the United States. These immigrants were individuals who had worked closely with the US military or held prominent positions in the South Vietnamese government and feared execution by the North Vietnamese communist authorities. This initial wave of migration faced a chaotic evacuation from their homeland, and they were often separated from family members. Upon arriving in the United States, they were processed at temporary resettlement camps scattered across the country, in California, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, and Florida. They were then transferred to live near sponsors who provided for their basic needs. The process of evacuating from their home country and being concentrated in temporary camps within the US while awaiting a sponsor was a unique experience, up until that point, only occurring with Southeast Asian immigrants. In 2022, after the sudden US withdrawal from Kabul, Afghanistan, 76,000 Afghan refugees were also temporarily housed in US military bases for several months, with some staying in hotels before being sponsored for resettlement.

The second wave of immigrants occurred a few years later, from the late 1970s until the mid-1980s. These immigrants left Vietnam after the communist regime sought to fundamentally change life in the newly unified Vietnam. Those considered a threat to the communist government faced re-education camps, which were essentially forced labor camps. Along with the second wave of migration were those who, for religious reasons or due to their economic status, were deemed guilty by the regime (e.g., capitalist merchants).

Countless refugees fled Vietnam on small, dangerous boats to neighboring countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, or Hong Kong, to await acceptance into refugee camps. From there, they sought to reach the United States, Australia, France, or Canada. However, due to the unsafe nature of these boats and the rampant piracy at sea, an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 Vietnamese perished during their sea journeys. For some Americans, seeking a better life was not an acceptable reason for immigration to the U.S., leading to a negative and dogmatic view of boat people arriving in the United States. However, the boat people's willingness to abandon their homeland and risk their lives to reach free countries demonstrated the desperation Vietnamese people experienced in the years after the fall of Saigon, which garnered more sympathy for them, even from previously leftist figures who had opposed the RVN government, such as philosopher Jean Paul Sartre. A major problem for the waves of Vietnamese refugees, especially the second wave (boat people), was Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) due to the horrors they faced leaving their country to come to the United States. People with PTSD often did not seek help due to the negative stigma associated with mental illness in the 1970s and 1980s. They often experienced nightmares, depression, and exhibited seemingly anti-social behaviors. The symptoms they experienced were similar to those of American soldiers with PTSD who had fought in Vietnam. This mental illness made it even more difficult for some refugees to integrate into American culture, find jobs, or integrate into their new communities in the United States. According to a 2006 study by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, about 70% of Southeast Asian refugees receiving mental health care were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

A significant difficulty in adapting to the new environment was the initial dispersal of Vietnamese immigrants. Sponsored immigrants moved throughout the United States, making it difficult for us, who came from a culture that relied heavily on family and community. A typical case is that of media personality L. N.. In 1975, at age 5, she evacuated with her family to the United States and settled in Minnesota, a very sparsely populated state with few Vietnamese. One day, her family found a vegetable in their backyard that resembled a Vietnamese vegetable, cooked it, and enjoyed it so much that they fell into a deep sleep. When their sponsors returned, they thought the whole family had food poisoning. However, this factor also helped her speak with an authentic American accent and succeed in the highly competitive environment of mainstream American television media.

As discussed above, generally, Americans were very dissatisfied with the Vietnam War. Vietnamese immigrants often faced racism and discrimination from American citizens, especially in the years after the Vietnam War. This anti-Asian sentiment began in the late 19th century with the Chinese and continued into the 1970s and 1980s. According to a 1975 Gallup poll, over half of the American public disapproved of the resettlement of Vietnamese in the United States. This attitude towards the influx of Vietnamese immigrants was due to Americans being tired of the war in Vietnam, while statistical data showed a tendency in the US to view Vietnamese as "enemies," even though most Vietnamese refugees had sided with the US in the war. Perhaps they misunderstood this as a war between the US and Vietnam, instead of being a civil war between South Vietnamese allied with the US and North Vietnamese supported by the communist world. There is no precise explanation for the data from the poll, but it made resettlement for post-war Vietnamese immigrants extremely difficult. Some high-ranking military officers of the RVN also faced difficulties with the US government and press, such as the case of Lieutenant General Đặng Văn Quang, who was denied a US visa for 15 years, as mentioned above. Another figure was General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan. When Saigon fell in 1975, General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan and his family approached the US Embassy for evacuation, but were refused. They escaped on a Republic of Vietnam Air Force plane and eventually were admitted to the US. Subsequently, the US Immigration and Naturalization Service attempted to deport him for alleged war crimes related to the summary execution of a communist prisoner named Nguyễn Văn Lém (Bảy Lốp) on February 1, 1968, during the Tet Offensive in Saigon. This event was captured in a famous worldwide news photograph by American photographer Eddy Adams, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1969. However, President Jimmy Carter stated "such historical revisionism was folly" and personally intervened to halt the deportation proceedings, allowing General Loan to remain in the United States. Mr. Lém was accused of massacring the family of RVN Lieutenant Colonel Nguyễn Tuấn, including his wife, mother, and six children. Only one son, Huân Nguyễn, 9 years old, survived despite being severely wounded by three gunshots and witnessing his mother die from blood loss. Huân later fled Vietnam after 1975 and immigrated to the United States. He became the first Vietnamese-American Rear Admiral of the United States Navy in 2019.

Despite general American public opposition to Vietnamese refugee immigration, the US government during President Carter's first and only term (January 1977-January 1981) enacted several policies to help refugees in the years following the Vietnam War. Former President Carter was one of the rare politicians who dared to choose a humanitarian but politically unfavorable policy, especially during an election period. When he passed away on December 29, 2024, Vietnamese refugees still remembered his gratitude. On October 28, 1977, President Carter signed HR 7769 into law, allowing Indochinese (Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian) to change their "parolee" status to "legal resident alien status" for official settlement in the United States, and to receive additional federal government assistance for English language learning, education, vocational training, and job searching. He stated: "Throughout my life, I have never seen any group of refugees that I know, so severely affected by war, as the Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian people". Previously, Indochinese refugees in the United States were granted a temporary immigration status called "parolee" under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975. This status allowed them to enter the United States and receive resettlement assistance but did not provide a path to permanent residency. In 1977, the law was amended to allow these refugees to adjust their status from "parolee" to permanent resident.

In 1980, as President Carter campaigned for a second term, the US economy was in crisis, with high unemployment and inflation, and his own political standing was challenged both domestically (Senator Edward Kennedy ran against the incumbent Carter) and internationally (Americans were held hostage in Iran). Accepting more immigrants could make Americans feel that their jobs were threatened. Nevertheless, President Carter still tried to persuade American voters to accept more "boat people" from refugee camps in Southeast Asia. In 1979, he ordered the 7th Fleet to rescue boat people at sea, temporarily increasing the maximum number of boat people accepted into the US to 14,000 per month, while also urging other leading nations to do the same. On May 17, 1980, President Carter signed the Refugee Act of 1980 into law, allowing for nearly a threefold increase in the number of boat people entering the US, from 17,400 per year to 50,000 per year. This was the first significant act, created to deal with the increasing number of refugees coming from Southeast Asia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The act precisely defined who could be classified as a refugee (main criterion: "well-founded fear of persecution": a person with a solid basis for fearing persecution if they return to their country of origin). The act also regulated naturalization for refugees. After one year of living in the United States, refugees were classified as permanent residents (granted green cards). After five years in the US, refugees could apply for citizenship. Vietnamese immigrants took significant advantage of this, evidenced by the fact that Vietnamese immigrants have the highest naturalization rate compared to other immigrant groups. This figure shows that Vietnamese immigrants at this time had no intention of returning to their homeland and that the US was their new home (although to this day, many overseas Vietnamese still call the US “đất tạm dung” or "temporary refuge").

2) Changes in the lives of Vietnamese Americans over 50 years.

After a few years in the US and having become more accustomed to their new land, Vietnamese immigrants moved to large urban areas to create "ethnic enclaves" with other Asian Americans. The most prominent example of these areas is "Little Saigon" in Orange County, California. More recently, the Vietnamese American population is around 2.2 million people, which is the largest number of Vietnamese living outside of Vietnam. The resettlement of Vietnamese immigrants into an Asian American community helped them easily adapt to such a new culture.

Fig. 3: Phước Lộc Thọ, known in English as Asian Garden Mall, the first Vietnamese-American business center in Little Saigon, Orange County (Source: Wikipedia)

Little Saigon, California, located in Orange County, has a population of about 190,000 people of Vietnamese descent, with the cities of Westminster (43,000) and Garden Grove (54,000). Located about 45 miles (72 km) south of Los Angeles, Westminster was once a predominantly white, middle-class suburban city in Orange County with much farmland, but the city later declined in the 1970s. In 1975, 50,000 Vietnamese landed at El Toro airfield at Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base. According to the Orange County Register (5/1/2015): "Marines set up a massive tent city on Camp Pendleton's dusty hillsides and ladled out bowls of beef noodle soup, buttered noodles, and steamed rice with sliced cucumbers. Some Marines opened their wallets to buy chopsticks [for the refugees]. Not everyone was as welcoming...At first, their attraction to conservative Orange County seemed an ill fit. At almost every turn, they were spurned, blamed, and told to be more like us. But it turned out their anti-communist politics, competitive spirit, and entrepreneurial hearts were like us".

Before the arrival of Vietnamese refugees in 1975 and the subsequent establishment of Little Saigon, the land in the Orange County area—especially Westminster, Garden Grove, and surrounding cities—was primarily agricultural, known for its orange groves, strawberry fields, and other crops. This area was characterized by its agricultural and rural nature, with most of the land considered undervalued and underdeveloped, not suitable for commercial or urban development at the time. In the mid-20th century, Orange County was generally in transition, with some areas experiencing suburban development due to post-war growth and the influence of attractions like nearby Disneyland in Anaheim. However, the specific area that would become Little Saigon remained relatively affordable and expansive, making it an ideal location for new immigrant communities to settle and establish businesses.

Since 1978, the heart of Little Saigon has long been Bolsa Avenue. Pioneers like Danh Quách opened a pharmacy with $37,000 in capital, and Frank Jao engaged in real estate. Frank Jao's Vietnamese name is Triệu Như Phát; he is of ethnic Chinese Vietnamese origin from Hải Phòng, immigrated to Đà Nẵng in 1954, and studied real estate at a community college after arriving in the US. He is currently one of four Vietnamese-American billionaires in the US, owning many large commercial establishments in Little Saigon, engaging in charity work, and serving as chairman of the Vietnamese Education Fund. That same year, the famous Người Việt Daily News also began publishing from a private residence in Garden Grove.

Other newly arrived Vietnamese Americans soon revitalized the area by opening their own businesses in former white-owned stores, and investors built large shopping centers with numerous businesses. The Vietnamese community and businesses then expanded into neighboring Garden Grove, Stanton, Fountain Valley, Anaheim, and Santa Ana. In 1988, a freeway exit sign was placed on the Garden Grove Freeway (State Route 22) indicating exits leading to Little Saigon.

The Vietnamese community in San Jose, California: Initial refugees were scattered across the United States under the sponsorship of organizations and individuals, but after some time, many moved to San Jose due to its warm climate, affordable housing, and job opportunities in Silicon Valley's growing technology industry, such as factory assembly jobs that did not require extensive knowledge or fluent English. In the late 1970s and 1980s, a concentrated Vietnamese area formed in East San Jose, with businesses and cultural hubs.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, San Jose had developed into an agricultural center, with a population including Mexican, Japanese, and other immigrant communities. By the mid-20th century, San Jose was predominantly white (98% in 1940), with significant Japanese American and Mexican populations, and was expanding rapidly due to post-war industrialization and suburban growth. Japantown was an important Asian community hub, while other Asian groups, including Chinese and Filipino immigrants, also contributed to the city's diversity before the large influx of Vietnamese refugees began in the late 1970s.

Vietnamese people have had a significant positive impact on San Jose's local economy. Research analyzing the 1980s showed that the influx of Vietnamese refugees led to a statistically significant increase in local wages, driven by higher consumption, productivity, and specialization, as well as the presence of government support programs. Vietnamese entrepreneurs established many small businesses—especially restaurants, nail salons, and markets—helping to revitalize commercial areas like shopping centers and contributing to the city's economic diversity and dynamism. Over time, the Vietnamese community has become a vital part of San Jose's economic fabric, especially in East San Jose, where their businesses remain important economic drivers.

Today, San Jose is home to over 180,000 Vietnamese, accounting for more than 10% of the city's population. Economically, Vietnamese Americans have established many small businesses, particularly in retail and food services, contributing significantly to the local economy. Despite challenges such as limited political representation and economic disparities, the community continues to grow and shape San Jose's cultural and economic landscape.

The Washington Metropolitan Area is another preferred destination for Vietnamese immigrants for several reasons. Many Vietnamese in the first wave of immigration had connections with the US government or embassy. Former Vice President Nguyễn Cao Kỳ initially opened a liquor store in Fairfax, Virginia, before moving to California. Other important figures such as General Cao Văn Viên and Lieutenant General Ngô Quang Trưởng settled permanently here.

Northern Virginia emerged as a suitable location in the region for resettlement for several reasons. A Washington Post article commemorating April 30, 1975, titled "They Built a Little Saigon in the Shadow of the Pentagon," recounted a Vietnamese refugee family establishing themselves in Clarendon after leaving Da Nang, Vietnam, and discussed the connection between Northern Virginia and countries influenced by the US, such as the Republic of Vietnam. Andrew Friedman, author of Covert Capital, discusses the connection between US involvement in building South Vietnam and the wealthy McLean residential area in Northern Virginia, adjacent to Washington D.C.. According to the Washington Post, "in the years leading to the bitter end of the war in Vietnam, when South Vietnamese engineers, officials, officers, or diplomats came to the US, they often settled near people they knew – government agents in Northern Virginia". In Northern Virginia, a small Vietnamese community of about 3,000 people was built partly due to years of cooperation with the US government. Embassy officials directed refugees here, and Arlington County had sponsors like the Catholic Church. After the first wave of immigrants settled in the Clarendon area, part of Arlington across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., existing family and social ties formed a network for future immigrants to join this demographic group. Initially, 15% (3,000 people) of the Vietnamese population in the US resided in the Washington, D.C. area, with many more joining later. The most densely settled Vietnamese areas in Northern Virginia are the Clarendon neighborhood along Wilson Boulevard and Columbia Pike, extending west to Falls Church and Annandale. Later, due to the gentrification and redevelopment of the Clarendon area after the metro line was built, Vietnamese businesses had to relocate, and the new destination was Eden Center, in the Seven Corners area, Falls Church City, Fairfax County. A Vietnamese lawyer, Mr. Nguyễn Văn Gioan, rented a long-closed Grand Union supermarket. His family pooled resources and divided it into many small sections for Vietnamese tenants. The name EDEN was chosen simply because it only had four letters, making the signboard less expensive, according to Ms. Gioan's recollection.

In 1984, the Eden Center mall opened, providing 20,000 square feet of affordable retail space to the area. In 1997, the Jewish owner reacquired the property, and 32,400 square feet were added to the Eden Center, as well as an iconic clock tower reminiscent of the Bến Thành market clock tower, an archway, and at that time, it was one of the largest Vietnamese shopping centers in the United States. Eden Center became a hub for Vietnamese commerce and activities. In 2007, "Exit Saigon, Enter Little Saigon," a traveling exhibition by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, temporarily located at Eden Center during its three-year nationwide tour, to tell the story of the Vietnamese American migration and adaptation experience in the US. Eden Center is now considered the concentration of Vietnamese services and goods in Northern Virginia, as well as the entire East Coast. In 2014, Eden Center housed 120 shops and restaurants, mostly Vietnamese-owned.

There are tensions between the police force of Falls Church, a small but wealthy city in the US with about 15,000 residents, and businesses at Eden Center. On August 11, 2011, federal agents, Virginia State Police, and local police jointly raided several businesses at Eden Center, seizing over $1 million in cash from one business and smaller amounts from others. They also seized some "slot machines". And 19 people were arrested on suspicion of gambling and alcohol crimes. Police blamed the Dragon Family gang, a Vietnamese American criminal organization operating in Asian American centers across North America. No felony charges were brought, and ultimately, although some defendants pleaded guilty, many cases were dismissed before trial. At least one defendant went to trial and was acquitted. The raid caused tension between Eden Center businesses and the City of Falls Church authorities. After a second raid, five months later, suspects were arrested on multiple gambling and money laundering charges, with many in the community alleging racial discrimination and poor investigation.

Currently, the Eden Center contributes over a million dollars in annual tax revenue to the city of Falls Church. The city has recently announced a long-term project to upgrade the Eden area and its surrounding vicinity. Local Vietnamese are also organizing to have a stronger voice in this improvement process while simultaneously preserving Vietnamese identity and preventing "gentrification" from displacing Vietnamese small business owners due to rapidly increasing prices.

Fig. 4: Eden Center, located in Falls Church, Northern Virginia, serving as a vital cultural and commercial center for the region's Vietnamese-American population. The designation of a portion of Wilson Boulevard as Saigon Boulevard directly fronting the shopping center emphasizes its role as a key symbol and gathering place for the community, reflecting their vibrant presence and cultural preservation efforts.

Some other commercial areas where many Vietnamese have done business for decades will gradually be replaced by large-scale, mainstream commercial establishments. For example, Graham Plaza at the corner of Arlington Boulevard and Graham Road previously housed the Harvest Moon Chinese restaurant, a popular venue for affordable community events and weddings, the famous Nha Trang grocery store which operated for over 40 years, and more recently, the well-known Golden Cow pho restaurant. All these establishments will be replaced by a large medical center comprising an outpatient clinic and various specialties of Virginia Hospital Center (VHC). This Tết (2025), the section of road in front of Eden Center was named Saigon Boulevard, marking a milestone of the Vietnamese community's presence in Virginia. A notable point for the Washington D.C. area, near the US capital, is that unlike other places like California, Vietnamese people here only concentrate their commercial activities in the Eden area. Their residences are not concentrated in one place; instead, they live interspersed with other ethnic groups, especially white people, in residential suburban areas. The relatively low-cost apartments near Eden Center, rented by newly arrived Vietnamese from refugee camps in the 1980s and 1990s, have now become preferred residences for a large number of Latin Americans who arrived in the decades after the early 21st century. Vietnamese only frequent this area for business and community activities, while their private homes are in wealthier condos, townhouses, or villas with better schools.

Fig.5: Commemorative plaque recording the history of Vietnamese settlement in Virginia, on Saigon Boulevard, in front of Eden Mall, Falls Church, Virginia

Houston, Texas, has one of the largest Vietnamese American communities in the United States. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there were about 85,000 Vietnamese Americans living in Houston, but this number could be as high as 150,000, as some individuals may not have been included in the official count.

Fig. 6: The Vietnamese Civic Center (Nhà Việt) in Houston, Texas, at 11360 Bellaire Blvd. This facility is a significant cultural, social, and educational resource for the large Vietnamese-American population in the Houston area.

The majority of the Vietnamese community in Houston resides in southwest Houston, particularly along Bellaire Boulevard, affectionately known as "Little Saigon" or Vietnam Town, Viettown, located within the International Management District. Because this neighborhood is adjacent to Chinatown, it is often mistakenly perceived as an extension of Chinatown. However, Little Saigon is a distinct neighborhood in itself. The section of Bellaire Boulevard was officially named Saigon Boulevard by the City of Houston, and intersecting streets also bear Vietnamese names. This area is bustling with Vietnamese-owned businesses, restaurants, markets, and cultural centers.

Hien V. Ho

May 21, 2023

April 28, 2025

Translated and edited by the author from the original Vietnamese version on 8/20/25.

For references, please go to the original article at