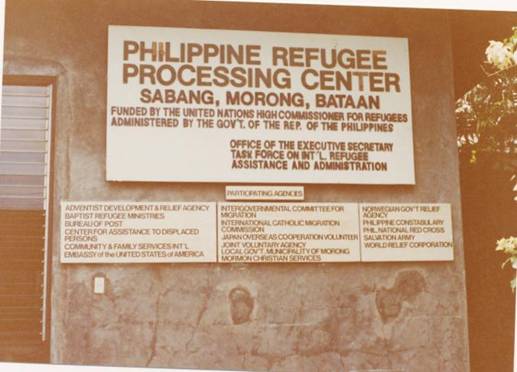

The Philippine Refugee Processing Center in 1981

From Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to Bataan in the Philippines.

We had spent more than 10 months in refugee camps in Malaysia before we were allowed to be resettled in the USA. However, at the last minute, due to a new policy of President Reagan’s administration, our flights to America were deferred, and we had to spend an extra 6 months of English classes and cultural orientation in the Philippines. On November 3,1981, after dark, we left Sungei Besi A, the transit camp for Vietnamese refugees in Kuala Lumpur, furtively. Large buses, brought us to the city main airport by its rear entrance. We were allowed to use the airport lobby only when everybody had left at midnight, and then only did we board the plane for Manila in the Philippines.

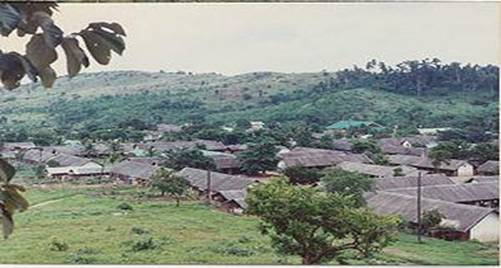

Figure 1: The camp in 1990

We arrived in Manila at night. A long caravan of buses took us to Bataan, a remote area, on the west coastline of the country. When we went through the streets of a Manila suburb, I was unable to see anything besides the lighted stores and the streetlights that reminded me of downtown Cholon, the giant Chinatown next to Saigon. After we left the city, the road was winding uphill, among the mountainous landscape. It was the first time in many years that I saw such a long line of lights on the road. Since 1975 most traffic that we had in Vietnam consisted of bicycles and military trucks, so any indication of modern life like the colors of traffic lights in Mersing, a taxi in Kuala Lumpur, a drinking water fountain at the airport, a neon store sign in Manila were encouraging signs meaning to me that we were making small steps toward civilization. My dream of coming back to the urban life ended when we arrived to the Bataan Philippines Refugee Processing Center (PRPC). It was really late and we were sent to a small house with the family of a friend. She was a former teacher whose husband, a lieutenant colonel in the South Vietnamese Parachutist Force, was still spending time in a communist concentration in North Vietnam. She traveled with two sons and two daughters.

Figure 2: View from above, the PRPC in 1990 (Credit Wikipedia)

Life at the Philippines Refugees Processing Center in Bataan.

The morning after, we were taken to our permanent living quarter. The PRPC was a village built from scratch with American money, just for the purpose of processing and preparing refugees who were heading for the United States. It had schools for children and adults, a community center where movies were shown on weekends, and facilities for its staff.

Adult education consisted mostly of Basic English at slightly different levels and orientation to American life style. The faculty was mostly Filipino, not surprisingly because the country was a former colony of the United States. People spoke English very fluently, with a small peculiar accent. A Catholic Sister, Sister Eugenia, was in charge of the orientation part. Refugees who had spent some time in the U.S. were recruited to the faculty and underwent 100 hours of training in the techniques of teaching.

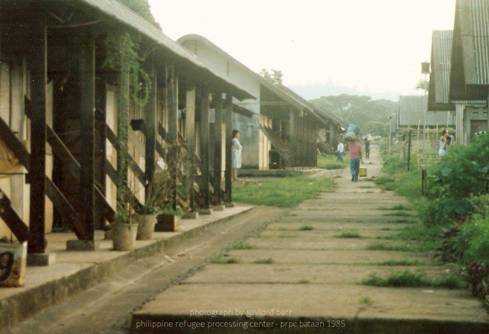

Figure 3: Freedom Plaza at the PRPC, with a boat from Vietnam in display

Before my escape I myself never went outside Vietnam but, because I was a doctor and spoke rather decent English, I also was drafted to the faculty. I taught the other teachers about basic medical knowledge, health care delivery systems and preventive medicine. It was done in English, and it seemed to me that the Sister appreciated it a lot. I never attended the orientation classes themselves, which were conducted in Vietnamese to the majority of the refugee students. They learned how to use an American bathroom, run a vacuum cleaner, or cook on a gas or electric range. There was even a small model house (a tiny one by our current standard) with everything from an American bed to a carpet floor. From our point of view at that time, it was like a dream house.

After the initial paperwork we moved in a small apartment about 3 meters by 4 meters in size, with a total surface area of around 120-130 square feet. An attic added some extra living space to our two families, 10 people in all, three adults and 7 children. My wife and I shared the large cot bed with our three children at night. My oldest son, though only 9 years old, did help with some of the housekeeping and babysitting for his mother.

The first disheartening sight we had was the apartment itself. The building was made of light material; walls were of thin concrete and roof of corrugated steel. There was a yard without trees in front. In the back there was a shallow moat full of black foul smelling water that probably was draining from some sewage nearby. As we entered the apartment, we were overwhelmed by a strong smell of human feces. The cement floor was littered with trash from the previous tenants and under the cot bed there were many remnants of bodily function products. We spent the whole day cleaning that mess. The condition of the communal outhouses, about ten yards away, later gave us an explanation why some people had elected not to use them. They were small buildings made of concrete, divided into narrow booths. Instead of toilet seats there were small gutters where people were supposed to relieve themselves without any sense of privacy. Above the gutters ran a water pipe with occasional copper faucets. Only a small stream of dripping water came out and it failed the purpose of flushing the gutters. Besides, those faucets also provided us with the only source of running water that we had. Every member of our family group had to take turns, spending 15 minutes to half an hour waiting for that water to trickle down and fill up a small bucket. Add to that the impatience in the waiting line and the strong stench from the gutters. That was how we got our washing, cooking and drinking water.

Figure 4: An alley in the camp (Image credit Gaylor Barr) (1985)

Fortunately, there were streams about half a mile from the camp. We followed a narrow, tortuous path leading to the valley and took bathes there. The scenery surrounding the streams was idyllic with green, exuberant tropical vegetation. The water was limpid and turbulent in places. Sometimes, it gave us the impression of being immersed in a whirlpool tub with its cool and singing stream, soothing our pain and worries. There was a place where water was deeper and overlooked by a shaded promontory. Some children could not resist the thrill of diving there and a few lost their lives doing so. However those streams of water were one of the few bright spots of my memory about Bataan.

Another fine moment was the celebration of the Vietnamese New Year. We had a fair where fake fire-crackers were hung from fake Vietnamese cherry trees. The pagoda was decorated with lookalike Chinese characters welcoming Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. For us, it was a day of painful nostalgia that marked another year in exile; and at the same time Tet, as always, brought us some amount of hope for the future. That night, we had a large bonfire that burned until the wee hours. I remembered that fire well because I was able to get a warm bath for the first time in years, from a bucket of hot water.

Another memorable event was our trip to Olongapo, a nearby Filipino city of about one hundred thousand inhabitants. The people there thrived on service provided to American servicemen stationed at the nearby military base of Bataan. We sneaked out of our camp because in theory we were not allowed outside. We boarded a small Filipino boat that took us to the city.

We shopped for a few cheap items. I bought my first Sony boom box and a little uni-focus, Instamatic Kodak camera that cost about 16-20 dollars. I was eager to spend that precious money because I wanted to have the pictures that would later become witnesses of the most memorable days of our life. One of my favorite pictures shows my wife in front of our apartment.

Figure 5: Olongapo colorful “Jeepneys” at Riza Plaza. Jeepneys, decorated American old military Jeeps from World War II are the most popular means of transportation in the Philippines.

(Photo credit: LA-ex.org)

Above her hangs a five pointed, star shaped paper lantern that I made myself from bamboo rods and paper for my children. It is a Vietnamese tradition to hang that kind of paper lantern during holidays like Christmas or Mid-Autumn Festival. Another picture shows my youngest son dancing with his daycare friends; another one has our children at a welcoming party when Mrs. Marcos, First Lady of the Philippine, came to visit us in her helicopter. I also remember my first ice cream in years that we had at a small restaurant where one of the Filipino teachers, Ms. Ninfa Alderette, took us. At night, we also had some entertainment at a few makeshift cafes at some refugees’ apartments.

On March 27, 1982 we left Bataan and boarded our charter plane in Manila, headed for Newport News, via San Francisco.

Figure 6: Pope John Paul II visited the camp and held a field mass for the refugees. The camp became a technology park, after having served a refuge for 400,000 people from Vietnam, Lao and Cambodia.

J. B. Ho

12-12-2008

4-11-2014

(This is an edited excerpt from the book “The Mayflowers of 1975”, edited by Chat V. Dang, Hien V. Ho, Nghia Vo, Than T An and Ann R. Capdeville. Illustrations were added to this online version.)