Nguyễn Trãi

The Ultimate “Kẻ Sĩ” (Scholar)

Nguyễn Trãi portrait from the 16th century,

at the Nguyen family worshipping temple in Hanoi, Vietnam

(Courtesy Wikipedia)

Nobility has five grades; scholars belong to them all,

Among society’s four classes, we rank first.

Recognized from nations’ beginnings,

Since the Zhou and Han, we are aristocrats.

Even village people know we are good at reasoning.

Therefore we have to uphold morality standards.

Our spirit, so great, so upright,

That it emulates the righteous spirit that fills Heaven and Earth.

When waiting for opportunity, we stay hidden in grass huts,

A simple life, fishing and working the land,

While waiting for an enlightened leader to come to invite us,

We educate the public with healthy debate...

When, as a cloud coming to meet a dragon, opportunity appears,

We use all our knowledge to act.

At court, we are the pillars of the government,

At the frontiers, we show off our legendary sword skills,

So that for generations will last our good reputation

First as scholars, then ministers and generals.

Statesmanship comes from our mind and heart,

Martial arts fill our beings,

Our duties call us everywhere in this world,

Only then we men deserve to be called heroes.

When the nation is at peace, we feel at ease

And live in seclusion...

Paying little attention to whether people ask about us,

Contemplating life, pondering who are pure and who are vulgar

Only then we can say we fulfilled our destiny.

Nguyễn Công Trứ[1]

In the Tradition of Confucius

Confucius (551-479 BCE) was China’s first private educator whose main purpose was to train young men for service in a meritocratic government, with emphasis on character formation based on moral learning. After the collapse of the Han in 220 CE, Buddhism from India, with its sophisticated metaphysics, competed for dominance with Taoism and reached a peak during the Tang dynasty (618-907). With the arrival of the Sung dynasty (979-1279), the Confucian tradition was reshaped and given a new life as “neo-Confucianism’. A long lost ascetical doctrine dealing with the cultivation of the mind was given a metaphysical frame to form a complete and totally native religion alongside with imported Buddhism. [2]

This transition from Buddhism to Confucianism in China occurred also in Vietnam. There was also a shift of Vietnamese society and culture from the early days of independence in the 11th century to the end of the 14th century, at the last days of the Tran dynasty and under the rule of Hồ Quý Ly who eventually usurped the throne to become King. According to legend, the founder of the Ly dynasty was conceived after his mother ‘met’ a deity in her dream, following a visit to a pagoda. At age 3, he was given for adoption, to the Buddhist monk Lý Khánh Văn, who then gave him the name of Lý Công Uẩn (974-1028). He became a chela, and after the age of 7, came under the tutelage of the famous Zen master Vạn Hạnh who later introduced him to the Le court.

Later, in 1010, Quý Ly was able to seize the royal throne from the sickly King Lê Long Đỉnh , also with Van Hanh’s help. Under the Ly Kings, hundreds of pagodas were built and Buddhism pervaded the life at the court as well as common people’s houses. For Confucianism, it took another 60 years before the first temple dedicated to Confucius and his disciples (Văn Miếu) was built in Thăng Long (Hanoi), and Confucius formal worship with full rituals started to be practiced twice a year in the capital, in the provinces and even at the village level. However, in 1227, Confucianism was still one of the three major religious topics in the newly established Three Religions Exam (thi tam giáo), and Buddhism remained the most venerated and privileged religion until the fall of the Trần dynasty. Hồ Quý Ly, who seized royal power in 1397 from his 5 year old grandson, and formally became king in 1400, tried to limit the power and influence of the Buddhist clergy. In 1396, still as a minister for the Tran, he asked the King to force Buddhist monks and Taoist priests under 50 to be defrocked. Regarding Confucianism, Hồ Quý Ly rejected interpretations of Confucius’ thoughts by the Song neo-Confucian scholars (Tống Nho), which constituted orthodoxy to the Ming Chinese. Hồ considered them to be out of touch with reality , and wanted to establish a brand of Vietnamese Confucianism, worshipping instead the Duke of Zhou (Chu Công) , architect of ancient Chinese feudal system established by the Zhou (1122-249 BCE). [3]

Nguyễn Trãi’s Origins: “Among five classes, we rank first”

Nguyễn Trãi was born in 1380, in Chí Linh, Hải Dương, Vietnam, and grew up in a predominantly Confucian milieu. His father, Nguyễn Phi Khanh, had earned a doctorate degree (bảng nhãn) but had to earn his living as a village teacher. He was not nominated for office because the Trần King disapproved of his marriage with the daughter of a high ranking mandarin, enforced after pregnancy. Only after Hồ Quý Ly toppled the Trần King in 1400 that he became a member of the royal secretarial staff (the “Royal Academy”), then Đại phu (high mandarin). For a few years in early childhood, Nguyễn Trãi lived with his mother and his grand father until her premature death. Afterwards, the five boys were moved to their father’s home at Nhị Khê (now Hanoi), where they received their intensive formation at home in classical Chinese and Confucianism from their father who wrote about his eldest son:

After the turmoil, the old garden still keeps its former house

At the age of six, my son already loves books. [4] [5]

At the age of 20, Nguyen Trãi passed the first exam in Confucian studies (rujiao, nho giáo) revamped by Hồ Quý Ly, and earned the doctorate title of Thai Hoc Sinh. The traditional exam to select literati for public office had been reorganized by the new Hồ King; one of his revolutionary changes was the creation of a mathematics exam in addition to the letters disciplines. It is interesting to note that mathematics in China, and therefore possibly in neighboring Vietnam, followed an independent path from mathematics in the western world. Besides the famous abacus used by Chinese merchants, every branch of western mathematics including arithmetic, algebra and trigonometry were well developed by the 14th century. [5] However, we do not know details about the mathematics exam instituted by Hồ Quý Ly. [6]

Ho Quy Ly’s Citadel, in Thanh Hoa Province, Viet Nam

Filial Piety

When the Ming Chinese invaded Vietnam, under the pretense of rescuing the Tran dynasty, Nguyễn Phi Khanh surrendered; Hồ Quý Ly, crown prince Hồ Hán Thương, and their close followings were arrested after their failed resistance war. All were taken to China where the former king would become a border guard in a remote village in Kim Lăng, Guangxi. Nguyễn Trãi, following traditional filial duties, wanted to accompany his elderly father. As they were crossing the Nam Quan gate, which marked the frontier between Vietnam and China, Nguyen Phi Khanh asked his son to stop following him and to “cleanse his country of its humiliation and to avenge his family.”

Opportunity: ‘Cloud meets Dragon’

After 10 years in hiding, spent in studies about the arts of warfare, or possibly travels to different sites in south China of which references were made in his later writings, Nguyễn Trãi decided to join the ranks of revolutionaries led by Lê Lợi (1384 (approx.) -1433). There is the possibility that Nguyễn Trãi joined Lê Lợi’s cause as early as in 1416, the year the latter initiated his movement against the Ming invasion, with a sworn brotherhood established with 18 friends in Lũng Nhai (hội thề Lũng Nhai, Thanh Hoá), which according to some sources, included Nguyễn Trãi. Two years later, the armed rebellion was started in Lam Sơn.

At Lỗi Giang in 1423, he presented to Lê Lợi a manuscript entitled Bình Ngô Sách (Strategy to Defeat the Wu), which persuaded the latter to assign him to the important position of adviser. The original text has been lost, but secondary sources point to three main themes of Nguyễn Trãi’s approach: to establish the righteousness of their cause (chính nghĩa); to recognize the strength of the people; and to win the support of the people rather than to conquer citadels. [7]

Nguyễn Trãi became Lê Lợi’s closest advisor for the whole length of the liberation war against the Ming Chinese.

All documents in diplomatic communications with the Chinese, proclamations made to the public or to the military were drafted by Nguyễn Trãi or under his direction. He is also known as a master of psychological warfare. There is a legend, well known to every Vietnamese school student, about his ruse in advocating the mandate from heaven of their cause. Reportedly, Nguyễn Trãi ordered his soldiers to write characters on tree leaves with a special concoction of fat and rice paste. Insects supposedly ate the tasty parts and left holes revealing these words on the leaves “Lê Lợi is the King, Nguyễn Trãi is his minister,” making friends and foes alike believe that it was a message from heaven.

Pillar of the Kingdom

After 10 years of struggle, at last, in 1428, Lê Lợi became the founding Lê King of the newly independent country, and Nguyen Trai became the most important minister of the court (Quan phục hầu or marquis). He was allowed to use the King’s family name and became Lê Trãi, and was allowed to enter and leave freely the royal residence.

According to Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư [7]

“The King used ‘soft’ power to fight ‘hard’ power, used weakness to win strength, therefore most of the times, it lead to victories. At Nghệ An, Thuận Hóa, Tây Đô, Đông Đô, he always asked Nguyễn Trãi to write letters [to the Chinese], explaining to them where their own best interests lay, therefore they surrendered without any need for us to attack, never causing any unnecessary killing. More than one hundred thousand Ming troops were caught prisoners, but we released them all. The King organized our country over a 10 year period, brought peace to a great war, and founded an empire” (Volume 2, p.257).

Honorable Reputation for Generations to Come

As the war ended and Chinese prisoners were returned to their country, Nguyễn Trãi penned the famous “Great Proclamation on the Pacification of the Wu” in classical Chinese, effectively an eloquent inauguration speech under Lê Lợi’s own name. An eulogy of the king’s achievement, it also contains statements to the effect that Vietnam was and had been a country separate from China, that the essential of politics was the well-being of the people, that the Chinese had purposely destroyed the Vietnamese environment, that the revolutionaries’ generous and humane treatment of the Chinese defeated troops was a wise and calculated decision.

The first paragraph in particular may be compared to a declaration of independence, with the extraordinary modern confirmation of the democratic principle “from the people, for the people, by the people”:

“The main objective of Humanity and Justice is the well-being of the people; military action is used only to eliminate violence. Our Dai Viet country has been a nation of civilization and culture. Mountains and rivers clearly delineate our borders, and customs in the South differ from those of the North.”

The next sentence has been often quoted by Vietnamese whenever their country runs into a hardship situation, such as economic woes or domination by a foreign country:”Although we had uneven periods of strength and weakness, we always have heroes among us”.

Especially relevant to our current ecological concerns is his condemnation of environmental crime committed through the Chinese policy of empire building in Ming China. The construction of the Forbidden City of Beijing, the Grand Canal of China, and Zheng He’s treasures ships under Zhu Di‘s reign (Yong Le, 1403-1424), required, among other things, destruction of hardwood forests in Vietnam. ”They bankrupted our people’s morality, the Proclamation said, destroyed our sky and earth, taxing us heavily, exhausting our mountains and rivers. They forced us to work in mines in spite of bad air pervading the mountains, to dive into the serpent-infested sea searching for pearls, to dig holes to set the traps for the black deer, to set nets to catch kingfishers. Our vegetation and our insects could not survive; lonely men, widows, homeless people lived in desolation.”

Finally, one of the most important statements that has been quoted again and again, by Vietnamese strategists and politician of all stripes, and by military and culture historians as the one characteristic of the Vietnamese philosophy in front of foreign aggressions, particularly vis-à-vis China, its giant neighbor and enemy in the north: “To use Great Righteousness to overcome violence, to use Humane strength to eliminate brute force “. [6] [8]

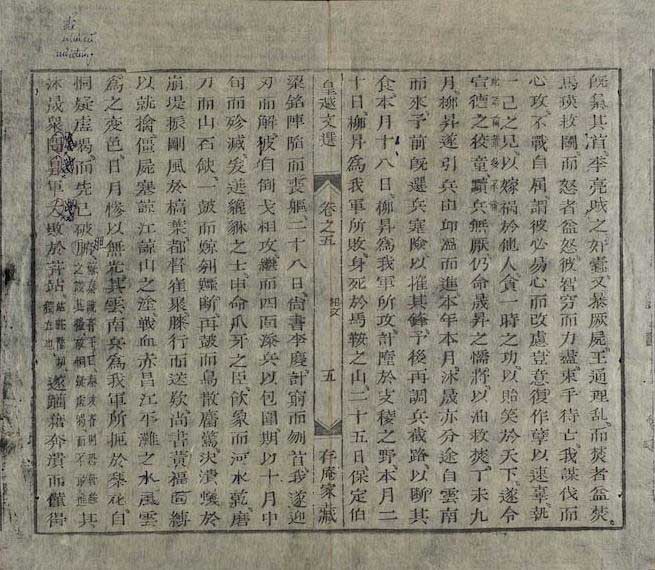

Great Proclamation on the Pacification of the Wu (from Hòang Việt Văn Tuyển, published in 1825)

Scholar first, then Minister and General

Following the Confucian literati model, Nguyễn Trãi was a prolific poet and writer in classical, literary Chinese. As for vernacular Vietnamese, significant literary use of written demotic Vietnamese (chữ nôm) only started in 1282 with Nguyễn Thuyên’s “Oration to the Crocodiles” (Văn tế cá sấu) , a copy of which to be ceremonially burned and thrown down to crocodiles to chase them away from a river. Nguyễn Trãi, as a pioneer in nôm writing, played an important role in the creation over the centuries of a body of literature in the national language, which culminated in Nguyễn Du’s masterpiece, “The Story of Kiều” in the 19th century, followed by modern Vietnamese literature in the 20th century.

His works included:

- Ức Trai Tập (Ức Trai Collection, Ức Trai being Nguyen Trai’s pen name [“hiệu”]), including annotated poems and writings of his father Nguyễn Phi Khanh.

- Văn Loại (Literary Varieties); including the “Great Proclamation”, the inscription on the commemorative stele for Lê Lợi in 1433. Nguyễn Gia Kiểng, a political activist and critic of traditional Vietnamese culture, considers the Proclamation to be the greatest literary masterpiece written in classical Chinese by a Vietnamese in the last 600 years [8].

- Ức Trai Thi Tập (Ức Trai Collection of Poems): a collection of more than one hundred poems in five and seven-word verses (ngũ ngôn, thất ngôn).

- Quân Trung Từ Mệnh Tập (the 4th volume of Ức Trai Tập), a collection of 24 messages, proclamations during the war against the Ming, including correspondence with Minh generals during the war.

- Dư Địa Chí (Volume 6 of Uc Trai Tap) (Treatise of Geography): Written in 1435, it was a study of history and descriptive geography of regions, mountains and rivers of Vietnam, their natural resources, and their administrative divisions.

- Works in nôm vernacular with the main purpose of teaching moral principles in rhymed, easy-to-remember, simple, day to day language :

1) Quốc Âm Thi Tập (Collection of Poems in National Language): a collection of 254 poems in nom, divided into 4 parts; using a large amount of people’s day to day language, incorporating many proverbs, sayings of his period. It is the oldest known collection of nôm poetry.

2) Gia Huấn Ca (Odes on Family Education): simple verses, in the Confucian tradition but quite full of common sense, teaching a woman to behave properly toward her husband (e.g. “Don’t be arrogant; use nice words, he will slowly change!”), her husband’s concubines (e.g. “Be charitable, she is a woman like you, but only less fortunate” ), his friends (e.g. “Don’t be mean to them, lest they would not respect your husband”), her servants, her in-laws, how to take care and educate her children (e.g. “Don’t let them play with a hammer or scissors, with fire, or near water; don’t overfeed them”), how to take care of herself during pregnancy (e.g.” Soothe your husband when you have a period”, “be careful in your bedroom when you are pregnant”).

Paying little attention to the outside world

Lê Lợi died in 1433. The young King Lê Thái Tôn who succeeded him was more interested in futilities, women and alcohol than in governing. In 1439, Nguyễn Trãi, at the age of 60 (counted the Vietnamese way to include the first year in the womb, and 60 being considered the expected life span), and feeling unwanted at the court, resigned to live in retirement in Côn Sơn, Chí Linh (the district of his birth ), in the province of Thanh Hóa.

Nguyễn Trãi had a young and beautiful concubine named Thị Lộ that he had first met when she was selling cheap sedge bed mats (chiếu gon) outside the royal palace. A playful exchange of poetry between the old mandarin and the 15 years old belle started their awkward love story.

He asked her first:

Where do come from, seller of cheap sedge mats?

Just wondering if you still have some left.

How many springs and autumns have you lived?

Are you married, with how many children?

She replied, in good concordance with the question’s rhymes:

I live at the Western Lake and I sell sedge mats

Why do you bother to ask if any are left?

My age, just above fifteen,

I don’t even have a husband, why asking about children?

As the king was dazzled by her beauty and literary skills, Thị Lộ had been named Lễ Nghi Học Sĩ (scholar in charge of etiquette) to teach ladies-in-waiting, and assigned as his “day and night” assistant during his travel.

In 1442, the young King went to review his troops and came to visit Nguyễn Trãi at his Côn Sơn rustic residence. Unfortunately, at the next stop at Lệ Chi Viên (Lychee Garden, Province of Bắc Ninh), after a sleepless night together, the king fell sick, had a fever and died while in her company. The court made the news public only after the dead king was brought home in the capital. Nguyễn Trãi was accused of regicide and given the traditional sentence of ‘tru di tam tộc’ (extermination of the three lines of ancestry, or execution of all members of the father’s, the mother’s and the wife’s sides of the convict). [9]

The legend of the avenging snake

Legend has it that Thị Lộ was the incarnation of a snake that wanted to avenge the death of its family. Many years before, Nguyễn Trãi was having a nap while his students were clearing some vegetation. In his dream, he saw a woman coming to him, accompanied by her children. She told him they were living in that corner of the forest with her family, asked him to spare their lives, and to allow them to stay for a few more days before moving to another area. Then Nguyễn Trãi was suddenly awakened by a commotion outside of his veranda. His students had discovered pit full of snakes of all size and they just killed all of them. That night, while his was reading, a drop of blood fell from the ceiling, made a red spot right on the character “đại” (generation), imbibed through the depth of three pages, presaging a vengeance carried on three generations. Also according to this legend, when the executioner’s blade fell on Thị Lộ, she transformed into a snake and slithered away.

At Nguyễn Trãi’s death, all his books, writings and documents were burned; only a few copies escaped destruction. One of his brothers and one of his sons escaped and survived the massacre. Two other children were later born to concubines who were pregnant at the time of his execution.

In 1464, Lê Thánh Tông, whose mother Nguyễn Trãi and Thị Lộ had rescued at the time of his birth from the conspiracy of one of his father’s concubines, reexamined his case and officially rehabilitated (chiêu tuyết) Nguyễn Trãi. An interesting modern interpretation of this legend argues that later Confucian historians, ashamed of a flagrant injustice inflicted on one of their own best, and of an embarrassing situation where a monarch died during a sexual liaison with his subject’s wife, tried to use the snake-turned-woman as a scapegoat.[10]

Eternal fame

Nguyễn Trãi is recognized as a national hero and the ultimate scholar-public servant by most Vietnamese, regardless of their political conviction or allegiance. An exception to this consensus comes from critics of the “kẻ sĩ” (Confucian scholar) mentality that they consider egocentric: self-cultivation, waiting to be called to serve by a deserving feudal head or King, followed by total loyalty and obedience to the death to his master.[10] However, like a protean figure used in a Rorschach test, Nguyễn Trãi’s legend has become the symbol of many different things dearest to the Vietnamese: academic achiever; military tactician and strategist; consummate diplomat; rhetorician; pioneer of vernacular nom writing; scientist; historian; writer; poet; and hero in a war of liberation.

In 1980, UNESCO recognized Nguyen Trai as a “Great Man of Culture of the World”. In 1989, after 6 years of research, Yveline Feray, French writer and Vietnam scholar, published a two-volume, 900 page, historical novel about Vietnam and China in the 15th century and centered on the tragedy of Nguyen Trai [11]

During the Vietnam War, Nguyễn Trãi was chosen as the patron-saint for the “political warfare” branch of the South Vietnamese republican army, while Northern leaders liked to use Nguyễn Trãi as a role model to emulate. Hồ Chí Minh grew up learning about Nguyễn Trãi from his Confucian-scholar-mandarin father. Official historians in socialist Vietnam nowadays like to point out the similarities between these two historical figures’ careers.

Most usefully for modern politicians in their concern about Vietnamese identity, Nguyễn Trãi’s legend offers the paradigm of a new Vietnamese thinking. After its relative economic success, Vietnam is trying to combine western know-how with East-Asian culture and humanism, a new but home-grown neo-Confucianism, outside of the currently revived Confucian tradition by China, which is using it to build its “soft power” dominance and to replace communist ideology.

Hien V. Ho, MD

November 11th, 2011

May 29th, 2014

This article is an edited version of a chapter from the book “ Vietnam History: Stories Retold For A New Generation”, by Hien V. Ho and Chat V. Dang, CreateSpace Independent Platform, 2012 (Available on Amazon.com)

http://www.amazon.com/Vietnam-History-Stories-Generation-Expanded/dp/1468186337/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1400847836&sr=1-1&keywords=vietnam+history+stories+retold

[1] From the poem “Kẻ sĩ”, by Nguyễn Công Trứ [1778-1858], a poet and a statesman, who like Nguyễn Trãi, is one of the most talented and fulfilled Confucian scholars in Vietnamese history.

[2] faculty.washingtonedu/mkaltonNeoconfucianism.htm

[3] Walter H. Slote, George A. De Vos, Confucianism and the Family, State University of New York Press, 1998, pp. 96-97

[4] Trinh Văn Thanh, Thành Ngữ Điển Tích Danh Nhân Tự Điển, Xuân Thu Publishers, 1966

[5] Wikipedia

[6] Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam Sử Lược, Bộ giáo dục, Trung Tâm Học liệu, Saigon

[7] According to Tự Điển Bách Khoa Tòan Thư, Ngô Thế Minh mentioned about the contents of Nguyễn Trãi Bình Ngô Sách in his preface to Ức Trai Di Tập , published under the reign of Emperor Minh Mạng.

[8] Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư, Bản In Nội Các Quan Bản (1697), Volume 2, Nhà xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội, Hànội,1992

[9] Phạm văn Sơn, Việt Sử Toàn Thư, Tủ Sách Sử học, p388-389 (reprinted in the USA)

[10]] Nguyễn Gia Kiểng, Whence…Whither…Vietnam? Paris 2005

[11] Yveline Feray,Dix Mille Printemps (Ten Thousand Springs), published by Philippe Picquier.

Addendum:

Bài Kẻ Sĩ của Nguyễn Công Trứ:

1. Tước hữu ngũ sĩ cư kỳ liệt

2. Dân hữu tứ sĩ vi chi tiên

3. Có giang sơn thì sĩ đã có tên

4. Từ Chu, Hán vốn sĩ này là quí

5. Miền hương đảng đã khen rằng hiếu nghị

6. Đạo lập thân phải giữ lấy cương thường

7. Khí hạo nhiên chí đại, chí cương

8. So chính khí đã đầy trong trời đất

9. Lúc vị ngộ hối tàng nơi bồng tất

10. Hiêu hiêu nhiên điếu Vị, canh Sằn

11. Xe bồ luân dầu chưa gặp Thang Văn

12. Phù thế giáo một vài câu thanh nghị

13. Cầm chính đạo để tịch tà, cự bí

14. Hồi cuồng lan nhi chướng bách xuyên

15. Rồng mây khi gặp hội ưa duyên

16. Đem quách cả sở tồn làm sở dụng

17. Trong lăng miếu ra tài lương đống

18. Ngoài biên thùy rạch mũi Can Tương

19. Làm sao cho bách thế lưu phương

20. Trước là sĩ sau là khanh tướng

2 1. Kinh luân khởi tâm thượng binh giáp tàng hung trung

22. Vũ trụ chi gian giai phận sự

23. Nam nhi đáo thử thị hào hùng

2 4. Nhà nưóc yên mà sĩ được thung dung

25. Bấy giờ sĩ sẽ tìm ông Hoàng Thạch

26. Dăm ba chú tiểu đồng lếch thếch

27. Tiêu dao nơi cùng cốc thâm sơn

28. Nào xe, nào ngựa, nào địch, nào đờn

29. Đồ thích chí chất đầy trong một túi

30. Mặc ai hỏi mặc ai không hỏi tới

31. Nhắm cuộc đời mà ngẫm kẻ trọc thanh

32. Này này, sĩ mới hoàn danh.