Người Việt Hải Ngoại Sau 50 Năm (1975-2025) (Phần1)

Vietnamese Overseas After 50 Years (1975-2025)

(Part 1)

Fig 1:Children on a boat formerly used by Vietnamese refugees in The Philippines Refugees Processing Center in Bataan, Philippines. (1982 Hien V. Ho)

The Spring of Ất Tỵ (Year of the snake) 2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the Vietnamese refugee and exile community, a journey that began with the end of the Vietnam War on April 30, 1975. Over the past five decades since the fall of the Republic of Vietnam, the global political and economic landscape has undergone significant changes. In the 1980s and 1990s, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the United States and the West maintained political and economic dominance worldwide. This afforded Vietnamese refugees settling in these nations a highly advantageous position compared to those in Vietnam, who faced severe impoverishment and isolation. Subsequently, the rise of China and, to a lesser extent, Southeast Asia and India, transformed Asia into a vast economic region, challenging Western supremacy. Following the implementation of the "Đổi Mới" (Renovation) policy in Vietnam in 1986 and the establishment of diplomatic relations with the United States, the economic disparity between overseas Vietnamese and those in their homeland gradually diminished. In the realm of science and technology, the world has progressed from the nascent digital age, through the explosive growth of the global internet, to the current era of artificial intelligence. Smartphones and platforms such as Viber, YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok have increasingly blurred communication and information barriers between Vietnam and the outside world, despite Vietnam remaining one of only five communist nations.

Over these five decades, this global community of exiled Vietnamese has grown to nearly 5 million people and has become an indispensable part of the societies in which they have settled. They have made significant contributions to the cultural diversity and economies of these nations, a vital condition for sustainable development in every country today, especially in the United States, which hosts the largest number of Vietnamese immigrants. These achievements are partly built upon a foundation of perseverance and adaptability, forged through trials of blood and tears in past challenges such as war, re-education camps, boat escapes, and refugee camps. These skills helped the exiled Vietnamese community overcome initial hardships and achieve remarkable success in various fields in their new homelands. Currently, a large number of Vietnamese within Vietnam still seek to join the overseas Vietnamese community, through both legal avenues (investment, studying abroad, marrying foreigners) and illicit means.

This article represents a highly subjective personal endeavor, without the ambition of being a comprehensive academic study. Its purpose is to reflect upon the historical context, adaptation efforts, and contributions of the exiled Vietnamese community over the past 50 years.

The Formation of the Overseas Vietnamese Community from 1975 to the Present.

A. In the United States:

a. The first wave of evacuation after the April 30, 1975 event, approximately 125,000 people.

The initial influx of Vietnamese arrived in 1975 as part of the 140,000 Indochinese initially evacuated under President Ford's order. These refugees, predominantly educated and possessing some English proficiency, were met with a warm reception from the American public, eager to assuage any lingering guilt regarding the abrupt departure of US forces from South Vietnam. By 1978, as the US economy began to decline, this initial warmth waned.

A notable event in the days leading up to the North Vietnamese army's occupation of Saigon was Operation Babylift. The organizer of the first flight that initiated this operation was Ed Daly, CEO of World Airways. He played a crucial role in rescuing South Vietnamese civilians as the South was on the brink of collapse. When North Vietnamese forces advanced near Da Nang, Daly defied US authorities and conducted daring evacuation flights from Da Nang using his company's Boeing 727 aircraft. Despite the chaos, overcrowding, and dangers—including rocket fire and mob violence—Daly managed to evacuate nearly 2,000 civilians in just two days. When US officials halted air rescues, Daly continued these deemed unauthorized missions, prioritizing women and children but often confronting desperate South Vietnamese soldiers. On one flight, he even resisted armed individuals boarding the plane and was wounded by gunfire. Daly also organized the first flight of "Operation Baby Airlift," converting one of his DC-8s into a "flying cradle" to transport over 50 orphans to safety in the United States. His audacious actions saved countless lives and remain a testament to his courage and compassion.

Fig.2: Danang Airport, on 3/29/2075

(https://www.aeroflap.com.br/en/the-boeing-727-that-was-shot-and-still-took-off-with-more-than-330-passengers-on-board/)

Following this initial flight on April 2, 1975, the US government continued to evacuate approximately 3,300 children from South Vietnam to the United States and other Western countries from April 3 to April 26, 1975, with the aim of rescuing orphans and other children. An interesting detail from this period: even Hugh Hefner, the controversial founder of Playboy magazine, lent his private jet, "Big Bunny," to support Operation Babylift, transporting 41 Vietnamese orphans from a distribution facility in San Francisco to their new families in New York. Throughout the flight, Playboy Bunnies cared for these children. This operation was marked by much controversy and tragedy. A C-5A Galaxy aircraft, part of the initial evacuation, crashed shortly after takeoff, killing 138 of over 300 people on board (figures vary depending on the source, likely due to the chaos and the fact that this plane was also used to evacuate personnel from the US Defense Attaché Office), including 67 women, which may have been kept confidential. Additionally, not all evacuated children were orphans, and adoption paperwork was often incomplete, leading to legal and ethical concerns. Although Operation Babylift was described as a successful humanitarian effort, it was sometimes criticized as a US attempt to embellish its intervention in Vietnam, as well as for the difficulties Vietnamese children experienced in adapting to the unfamiliar environment of Western society. Only about 12 individuals managed to find their birth parents.

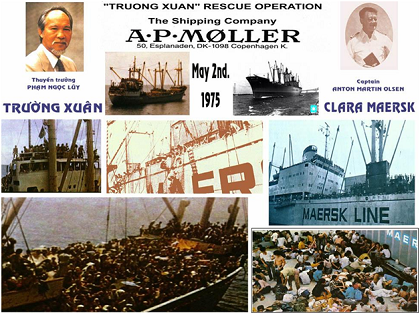

Fig.3: Captain Pham Ngoc Luy, the ship Truong Xuan, and Anton Martin Olsen of Clara Maersk who rescued the Vietnamese in distress.

A noteworthy story from the period around April 30 is that of the ship Trường Xuân, a private transport vessel owned by Mr. Trần Đình Trường's Vishipco company. The owner had traveled with his family to Manila on a private vessel; but, as he recounted, before fleeing, he instructed his trusted associates to use as many ships as possible to transport people out of Vietnam. He arrived in the US with two suitcases full of gold and invested in budget hotels in New York. After April 30, Vishipco company was nationalized by the new government, and the company's inheritors had to sue the American Chase Manhattan bank for a long time to reclaim deposited funds (South Vietnamese dong, piastre) at this bank before Saigon fell. He became the first Vietnamese billionaire in the US, actively helping the Vietnamese community and donating millions to various charities in the US and Africa.

The ship Trường Xuân was docked at Saigon port at that time. In late April 1975, the ship, commanded by Captain Phạm Ngọc Lũy, departed Saigon carrying 3,628 refugees amidst the fall of Saigon. The cargo ship was overloaded, damaged, and began to sink on May 2, 1975. The Danish ship Clara Maersk, commanded by Captain Anton Martin Olsen, rescued all passengers and took them to Hong Kong. Subsequently, many of these refugees were resettled in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Australia. This heroic rescue is remembered as a significant milestone in the history of Vietnamese refugees.

b. The second wave consisted of "boat people," peaking in 1978-1979 (the year of border wars with Cambodia and China) and continuing until the mid-1980s.

Ultimately, Indonesia closed its refugee camp in Galang in 1996; Thailand in 1997; the Philippines in 1997; and Hong Kong in 2000. In 2001, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees officially dismantled the last refugee camp located in Malaysia, ending 21 years of UNHCR cooperation in that country to assist boat people from Vietnam.

Regarding ethnic Chinese Vietnamese, in the South, local authorities permitted them to leave Vietnam "semi-officially" on ships sometimes carrying hundreds of people, supervised by police (who collected travel fees in gold) when boarding. However, sometimes their ships were later intercepted by police in other localities, and they were imprisoned. In the North, due to unofficial pressure from the government and new discrimination and harassment from local people who had previously treated them as compatriots, around 260,000 ethnic Chinese refugees—primarily farmers, fishermen, and artisans—fled Vietnam during the brief border war in 1979 after Vietnam invaded Cambodia. According to the UNHCR, by 2007, their numbers had increased to at least 300,000 in China, becoming one of the most successful local integration programs in the world. Some, after arriving at refugee camps in China, crossed the border by land and sea to Hong Kong. After a difficult time living in refugee camps, some were repatriated to Vietnam, while others were settled in the West.

c. The third wave occurred in the 1980s-1990s.

In response to the hardships endured by boat people and following the Geneva Conference on Indochinese Refugees on June 14, 1980, the US government allowed Vietnamese to immigrate to the US through the Orderly Departure Program (ODP) of UNHCR. The following groups were settled in the US under these programs: family reunification, former US employees, and former re-education camp prisoners. Former re-education camp prisoners immigrated to the US through a subprogram of ODP called the Humanitarian Operation (HO). The Orderly Departure Program helped over 500,000 Vietnamese refugees immigrate to the US before the program ended in 1994. In November 2005, the US and Vietnam signed an agreement to reopen ODP and extend the McCain Amendment (allowing children of former re-education camp prisoners to immigrate with their parents). The ODP extension ended in February 2009, with the McCain Amendment expiring in September 2009.

In 1987, the US Congress passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act, allowing Vietnamese children with American fathers to immigrate to the US, permitting an estimated 23,000-25,000 Amerasians and 60,000-70,000 of their relatives to immigrate to the US.

B. Vietnamese refugees settling in Europe:

1) Vietnamese in France tend to have a higher level of education and better living standards than those settled in North America, Australia, and the rest of Europe. This could be due to their familiarity with French culture, as many wealthy Vietnamese families had settled in France before the war between North and South Vietnam occurred.

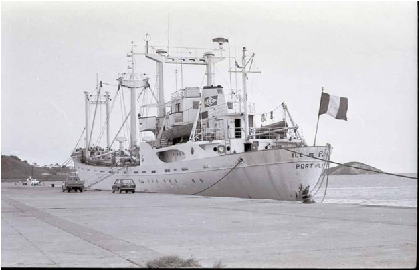

Fig. 4: In 1978, the boat "Ile de Lumière" was chartered to rescue the "boat people." The political and intellectual consensus was unanimous, and the mobilization of the population gave rise to a new concept: humanitarian rescue at sea. (https://seatizens.org/ile-de-lumiere-sauvetage/)

The Vietnamese community in France is estimated to be between 300,000 and 323,000 people, making it the largest non-English-speaking Vietnamese community globally. Approximately half of this population resides in Paris and the Île-de-France region, with significant numbers also living in cities like Marseille and Lyon. Two notable cases include the collaboration of French individuals in various fields to create the "Île de Lumière" (Island of Light) hospital ship, which rescued boat people along the Vietnamese coast at the behest of Dr. Bernard Kouchner, founder of "Doctors Without Borders." The second instance involved the French President Jacques Chirac informally adopting a young Vietnamese refugee girl Anh Dao Traxel when he was Mayor of Paris in 1979.

The Vietnamese community in France exhibits a higher degree of assimilation into mainstream society compared to Vietnamese communities in English-speaking countries, owing to their cultural, historical, and linguistic ties and understanding with the host country. They integrate well into French society but maintain strong ties to their homeland. Conversely, later generations of Vietnamese in France are more connected to French culture than Vietnamese culture, as they were raised and educated within the French system, which is a homogeneous, centralized, non-diverse; unlike the education system in the US which is more multicultural and has more variations as it is mostly controled by different states and local goverments.

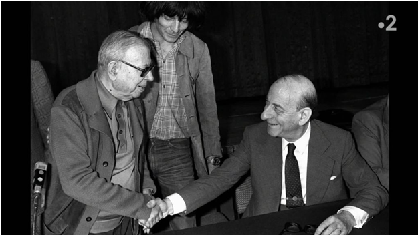

Fig.5: Sartre, Aron, and Glucksmann on the steps of the Élysée Palace: intellectuals of all stripes rally for a good cause! (https://seatizens.org/ile-de-lumiere-sauvetage/)

Jean-Paul Sartre, Raymond Aron, and André Glucksmann were prominent French intellectuals who, despite significant philosophical and political differences, collaborated in 1979 to advocate for the plight of the “boat people”—refugees fleeing Communist Vietnam and Cambodia after the Vietnam War. This collaboration was significant in French public life and the European intellectual response to the humanitarian crisis. Jean-Paul Sartre was a leading existentialist philosopher and writer, known for his left-wing activism. Raymond Aron was a renowned philosopher, sociologist, and political commentator, often seen as a critic of Sartre’s Marxist leanings but respected across ideological lines. André Glucksmann was a philosopher initially aligned with the French far left, but later a critic of totalitarianism and Communism. He played a key role in persuading both Sartre and Aron—old friends whose relationship had been marred by political disagreements—to unite in supporting the refugees.

Many Vietnamese have established businesses such as restaurants, supermarkets, and other small enterprises. Vietnamese rice farms have also been established in southeastern France. A significant portion participates in professional fields such as medicine, engineering, and academia. Some notable figures include two history professors, Lê Thành Khôi and Nguyễn Thế Anh, the dissident North Vietnamese journalist Bùi Tín, literary critic Đặng Tiến, and singer Bạch Yến, who passed away in recent years. Many former medical professors from the Saigon Medical School as well as many doctors from the Republic of Vietnam settled in France. They continue to practice medicine, socialize and publish newspapers regularly in Vietnamese after 50 years since the fall of their country. In general, the high educational attainment of Vietnamese-French people contributes to their success in these fields.

Some artists and writers initially settled in France, but later moved to the US, especially California, for more convenient creative and business opportunities. The variety show "Paris by Night" (PBN) has been very successful within the global Vietnamese community, founded by Mr. Tô Văn Lai in 1983 in Paris to fill the "cultural void" for Vietnamese who came to France in the 1960s-1970s. However, it later moved to Orange County in the US after he learned about the huge sales of Asia's music tapes by musician Anh Bằng in the US. Subsequently, PBN became a global cultural phenomenon for the Vietnamese community. Musician Lam Phương (1937-2020) left Vietnam on the aforementioned ship Trường Xuân (composing the song "Con Tàu Định Mệnh" - The Fated Ship), went to the US, lived a very difficult life, and sought "love refuge" in Paris for a period before returning to the US in 1995. After earlier generations from the first half of the 20th century worked as factory workers, railroad constructors, and other manual laborers, later generations diversified into higher-skilled professions.

In France, although recent immigrants have faced negative publicity, Vietnamese are considered "exemplary," with differences in historical background, socioeconomic circumstances, and integration experiences. They arrived as students, workers, or soldiers during the colonial period, and after 1975 as refugees, including educated professionals and middle-class individuals fleeing communism. They were often warmly welcomed by both the French government and society, partly due to their refugee status and partly because the French wanted to maintain a “soft power” leadership role in the context of the Cold War between the two main military powers, the US and the communist bloc. They also have high rates of naturalization and intermarriage with the French population.

Unlike Vietnamese refugees in the United States, the French community is divided into two significant factions: those sympathetic to Hanoi, primarily comprising students, workers, and long-term exiles; and those opposed to Hanoi, with support from Southern Vietnamese students and the middle class. Most of the anti-Hanoi faction, the smaller of the two groups, fled Vietnam after 1975. Despite their differences, both groups remain deeply connected to their homeland.

2) In the UK, the Vietnamese community is only about 28,000 people, mostly in the capital region of London, predominantly from Northern Vietnam and of Chinese descent, from the evacuation wave after April 30, 1975, and a subsequent wave during the war between China and Vietnam (1979).

Vietnamese immigrants to the UK have recently been frequently mentioned due to groups of immigrants attempting dangerous means of entry, such as hiding in trucks to cross the English Channel from France to England. Most notably, on October 23, 2019, in Essex, UK, a refrigerated container was discovered with 39 Vietnamese people who had died from suffocation and cold after being smuggled from Belgium. According to the BBC (July 15, 2024), Vietnam is in the "top 10 countries" with the most citizens crossing the sea to the UK, according to statistics for 2023 (as of the end of March 2024) from the UK Home Office. With 2,338 people crossing the English Channel in small boats, Vietnam ranks 7th, behind only Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Eritrea, Syria, and Iraq. Also according to the BBC, the Forced Migration Review (FMR) of the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford (UK) states that Vietnam is one of the leading countries in terms of the number of illegal immigrants to Europe. According to FMR statistics, the majority of Vietnamese illegal immigrants to Europe are male teenagers from some provinces in the North and North Central regions. A person specializing in helping Vietnamese enter the UK named Thanh revealed to a BBC reporter that the cost of the trip across the UK border is 10,000 to 20,000 US dollars, double the usual price for other nationalities, so Vietnamese are prioritized. Thanh said he wants people in Vietnam to understand that job opportunities for making money in the UK are no longer as good as before and no better than in countries like Germany on mainland Europe, and that people in Vietnam should understand that accumulating a large debt to arrange and secretly enter the UK to work in the "grey economy" (illegal) is not worth doing.

C. Vietnamese community in Australia:

Before 1975, fewer than 2,000 people of Vietnamese origin lived in Australia. On April 26, 1976, the ship named Kiên Giang, about 20 meters long, carrying the first 5 refugees fleeing Vietnam, arrived at Kiwi Island north of Darwin harbor after three months at sea, with the boat driver navigating by a map torn from a textbook atlas. The group's representative, Lam Binh, introduced himself and his group: "Please come down to my boat. My name is Lam Binh, and these are my friends from South Vietnam, and we would like permission to stay in Australia."

After April 30, 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam of the Labor Party advocated for severely limiting Vietnamese refugees entering Australia. By the end of 1975, only 400 refugees were selected from camps in the region and arrived in Australia by plane, not by boat. (Whitlam lost the premiership in November 1975, replaced by Fraser). It was not until 1978, under Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser of the Liberal Party, that Australia had a significant Vietnamese refugee resettlement program, allowing 60,000 Vietnamese to settle by 1982. At Fraser's funeral in 2015, members of the Vietnamese community attended in large numbers to pay their respects, with one Vietnamese leader stating, "We are refugees from Vietnam and my family came to Indonesia as refugees, and thanks to Malcolm Fraser's policy at that time, we were welcomed to Australia as refugees in 1979." Fraser's support for multiculturalism and compassion for Vietnamese refugees is considered a significant part of his prime ministerial legacy.

After the first wave of refugee intake in the late 1970s, there was a second wave of immigration in 1983–84, resulting from a 1982 agreement between the Australian and Vietnamese governments (the Orderly Departure Program) that allowed relatives of Vietnamese Australians to enter, leave Vietnam, and migrate to Australia. A third immigration peak in the late 1980s appears to have been mainly due to Australia's family reunion program. In the 2021 census, 334,781 Australians reported Vietnamese ancestry, accounting for 1.3% of the Australian population. In 2021, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 268,170 Australian residents were born in Vietnam. The Vietnamese community in Australia is smaller than the Vietnamese community in the US, but compared to Australia's population of 26 million, the proportion of Vietnamese in Australia is higher than in the US (2.2 million Vietnamese out of a population of 333 million, or 0.66%). Approximately three-quarters of people of Vietnamese origin live in New South Wales (40.7%) and Victoria (36.8%). The Nguyen surname is the seventh most common surname in Australia (second only to Smith in the Melbourne phone book). According to the 2021 census, Vietnamese is spoken at home by 320,760 people in Australia, making it the fourth most widely spoken language after English, Mandarin, and Arabic. (according to English Wikipedia). Generally, the educational attainment and household income of people of Vietnamese origin in Australia are higher than the average for other immigrant groups; in the US, Vietnamese have a median household income of 81,000 US dollars, lower than the average for people of Asian descent.

An interesting success story: Mr. Hiếu Văn Lê served as the 35th Governor (mostly ceremonial, representing the Queen of England as Australia's head of state) of South Australia from September 1, 2014, to August 31, 2021. He was the first person of Asian descent to be appointed governor of an Australian state and the first person of Vietnamese descent to hold a semi-regal position worldwide. He arrived in Australia as a refugee in 1977 and has been active in promoting multiculturalism and supporting the Vietnamese community in South Australia.

D. Vietnamese community in Canada:

Before 1975, there were only a few thousand Vietnamese living in French-speaking Quebec, mostly students. From 1975 to 1985, 110,000 Vietnamese were resettled in Canada. The first Vietnamese refugee was the film actress Kiều Chinh. Let's learn more about her case to see how, fifty years ago, during that period of uncertainty, when the country was in turmoil, the fate of stateless Vietnamese was so precarious, unlike today's "immigrants" who can simply reach the borders of countries like the US, France, UK, Italy, "claim" asylum, and be temporarily accepted pending review by the host country's immigration courts. This case is similar to the situation of faculty members from the Saigon Medical University who were studying in the US when Saigon fell. Overnight, suddenly, titles such as professor and lecturer from Saigon University were no longer recognized, and they were suspended from their jobs, having to re-apply for credentials from scratch to qualify as a foreign medical graduate seeking the lowest position (intern) in an American hospital.

According to VOA Vietnamese: "Kiều Chinh was on an endless round-the-world flight. The plane landed at airports in the most glamorous cities in the world, but no city opened its doors to welcome the top film star of South Vietnam because Kiều Chinh suddenly became a stateless person, carrying a diplomatic passport of a government no longer recognized. 'I understood that I had to leave. At that time, leaving was not easy, even though I had a diplomatic passport in my hand. When I arrived in Singapore, I was immediately thrown into prison because her diplomatic passport was no longer valid. They said that her passport belonged to a government that no longer had power,'.... That was an unforgettable moment in the tumultuous life of the former South Vietnamese film star, when Kiều Chinh realized her stateless status and deeply felt her immense loss in the last days leading up to the April 30, 1975 event. Losing everything – family, money, fame – Kiều Chinh became an illegal immigrant in a place where, just over a week before, she had been sought after as a movie star in a hit film, which had just finished shooting on April 15, 1975. Going against her family's advice, she had returned to a dying Saigon. Hurriedly leaving a week later, she paid a heavy price for that decision. With the intervention of diplomats and friends, Kiều Chinh was released from prison on the condition that she immediately leave Singapore. After an endless round-the-world flight, Kiều Chinh landed at Toronto airport at 6 PM on April 30, 1975, and automatically became a refugee. Like hundreds of thousands of other refugees, Kiều Chinh experienced the bitterness of a changed life, having to rebuild everything from scratch to eventually become one of the most well-known Vietnamese-American actresses in Hollywood. Kiều Chinh never forgot the phone call that helped her escape the hardship of cleaning chicken coops during her early refugee days in Canada. Spending all her savings, Kiều Chinh called several colleagues and old friends in Hollywood. Disappointed not to reach anyone, she risked her remaining money on one last phone call and connected with a woman she had only met once in Saigon: American movie star Tippi Hedren.

"I just called on a whim, but I was surprised when she picked up the phone. I said, 'Tippi, this is Kiều Chinh, the Vietnamese actress from Saigon. We met 10 years ago, do you remember?' She said, 'Oh, I'm so happy, so happy! When Saigon fell, I thought of you. I didn't know if you were alive or dead, or where you were.' I burst into tears, saying I didn't have any money left to continue talking, please call back. That's when I told her about my situation. She said, 'Don't cry anymore. Everything will be OK.' She opened her arms and heart and helped me. She bought my plane ticket for me from Toronto to Hollywood," Kiều Chinh recounted emotionally. (End of excerpt)

After that, Kiều Chinh settled in the US and rebuilt her film career in Hollywood. Ms. Tippi Hedren would pave the way for the Vietnamese nail industry in the US as well as other developed countries.

Subsequent waves of Vietnamese refugees in Canada:

a) The relatively small first wave consisted primarily of middle-class individuals evacuated from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon.

By the end of 1975, approximately 6,000–7,000 Vietnamese had arrived in Canada. Some were refugees under the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, while others were reunited with family and relatives in Canada. The majority, about 65%, were educated French speakers who settled in the Montréal area. From 1976 to 1977, Canada accepted only 630 refugees, partly due to the scandal surrounding the arrival of former General Đặng Văn Quang in Montréal, who was accused of war crimes.” This is a case that shows former leaders of the South were not always welcomed with a red carpet in the land of their former allies. Around 1965, Lieutenant General Đặng Văn Quang was the commander of the IV Corps Tactical Zone (Mekong Delta) and later served as national security advisor to President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, working closely with US officials. After April 1975, with US assistance, he and his family of seven children were settled in the US and Montreal, Canada, where French-speaking Vietnamese could integrate more easily. However, after visiting one of his sons in Montreal in May 1975, his application for re-entry into the US was rejected by the US State Department. No official explanation was given, but around that time, Canadian and US news sources began to accuse General Quang of having controlled heroin trafficking in the Mekong Delta during the war and secretly transferring millions of dollars into Swiss bank accounts. He was considered an "undesirable alien" in Canada, and the only thing preventing the Canadian government from deporting him back to Vietnam was the prospect of him certainly facing the death penalty if he returned to his communist-ruled homeland. For the next 15 years, General Quang worked as a dishwasher and did odd jobs in Montreal to support his wife and two sons. Appeals from his family in the US and military officers defending his character sent to the US State Department were ignored. The United States seemed to have washed its hands of him. It was not until 1986 that former US Special Forces Lieutenant Colonel Dan Marvin discovered General Quang's situation and subsequently offered to help him. At first, the general could not recognize the American's name among the many US officers he had known during the war. General Quang had previously pardoned Marvin and the Hòa Hảo soldiers he had trained who were considered rebels in An Phú district, near the Cambodian border in 1965, before they were about to be annihilated by RVN troops due to orders from central command who wanted to punish them. And now it was time for Marvin to repay that life-saving favor. Marvin launched a campaign to clear General Quang's name in the US, proving he had been a valuable ally to the US, and finally, in 1989, personally drove him back to the US after 15 years of being denied a visa.

b) The second wave included "boat people" from South Vietnam, and after Canadian immigration laws became more liberal, especially after the Hai Hong ship incident was denied entry to Malaysia.

In 1976, the Canadian government enacted a new Immigration Act to allow more groups of people than before to enter Canada, and for the first time, this law included refugees as a separate class of immigrants. A special category of refugees, the Indochinese Designated Class, was established to expedite the processing of these refugees and bring them to Canada sooner. In November 1978, after Malaysia refused to allow the Hai Hong cargo ship carrying 2,500 refugees ashore, Canada accepted 600 refugees from this ship, and many other countries offered to resettle the rest. This marked a turning point in Canadian attitudes. Just before the UN Meeting on Refugees and Displaced Persons in Southeast Asia in Geneva in July 1979, the Canadian government announced it would accept 50,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Half of the refugees would be government-assisted and the other half would be privately sponsored by Canadians. Many of them were ethnic Chinese who fled ethnic persecution due to the war between Vietnam (unified and communist) and China in February-March 1979, after Vietnam sent troops into Cambodia to overthrow the Khmer Rouge government. In 1979–80, Canada accepted 60,000 Vietnamese refugees. They were sponsored by churches, pagodas, and private individuals in various regions across Canada, but gradually they moved again to major urban centers. The next wave of Vietnamese migration arrived in the late 1980s when both refugees and post-war Vietnamese immigrants entered Canada. These groups settled in urban areas such as Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Calgary. By the 1990s, when Vietnam's economy opened up and the Vietnamese government implemented the "Đổi Mới" policy, the number of Vietnamese entering Canada decreased significantly. As of 2021, there are 275,530 Vietnamese Canadians, mostly residing in the provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec, accounting for 0.7% of Canada's total population of 39 million people. Mr. Thanh Hai Ngo (born 1947) is the first person of Vietnamese descent to serve as a Canadian Senator (in the Canadian government, the position of Senator is not elected by the people and does not hold legislative power like in the US). Another figure in politics is Ève-Mary Thaï Thi Lac (born 1972). A person of Vietnamese origin, adopted by a Quebec family at the age of 2 and raised on a farm, she is proud to be the only one in the election who knows how to castrate pigs, and was elected to the Canadian House of Commons in 2007 despite facing discrimination.

E. Current situation of Vietnamese emigration:

According to statistics from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), on average, over 100,000 Vietnamese emigrate each year, most of whom are educated or high-income individuals within the country, and Vietnam is among the top 10 countries with the most international students worldwide (according to SBS, Australia). According to the International Labour Organization (ILO): "A total of approximately 80,000 Vietnamese workers leave the country to work abroad each year. Around 400,000 Vietnamese laborers are currently present in over 40 countries and territories worldwide. The annual remittance flow from migrant workers reaches about 2 billion USD, according to English Wikipedia, in recent years, showing the economic significance of labor migration. Unfortunately, there are also significant problems associated with labor migration: employers violating workers' rights, workers violating contracts and deserting, illegal recruitment networks, and most notably, violations of government regulations on recruitment procedures."

F. Some historical milestones regarding Vietnamese living abroad.

a. The first large wave of Vietnamese leaving their homeland for the West was around 1914-1918, during World War I, when 50,000 Indochinese (Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian) laborers and 50,000 soldiers were sent to reinforce French labor and military forces. However, most of these individuals returned home after the war. In the 1920s, only about 8,000 Vietnamese remained in France, mostly military personnel.

b. The second wave of migration (temporary and forced) of Vietnamese "worker-soldiers" to France occurred in late 1939 before the brief war between France and Germany, when World War II began. The chaotic situation during the period after France surrendered to Germany (Marshal Pétain's Vichy government) and the events when France was liberated by the Allies in 1945 delayed the repatriation of these worker-soldiers, and their repatriation only ended in 1952.

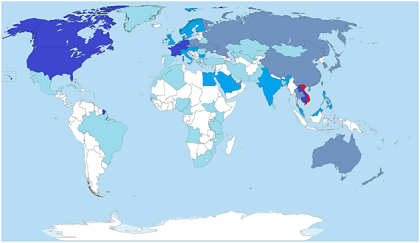

Fig. 6: Overseas Vietnamese population by country. Vietnam is marked red. Darker blue represents a larger number of overseas Vietnamese people by percent. (source: Wikipedia)

c. Currently, there are about 4.5 million people born in Vietnam or of Vietnamese descent living overseas. About half of this number live in the US (Vietnamese Americans), and surprisingly, Cambodia is the second country in terms of the number of Vietnamese immigrants. This number is estimated to be between 500,000 and one million people, with 90% being "stateless" and lacking identity cards or birth certificates. After the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia in 1975, most Vietnamese fled the country, with only about 20,000 remaining, and most were killed. Afterwards, Vietnamese began to return to Cambodia from Vietnam.

Regarding South Korea, it is the number one destination for Vietnamese brides. According to 2020 data, among 2,036,075 foreigners residing in South Korea, Chinese accounted for 44%, equivalent to 894,906 people. In second place were Vietnamese with 211,243 people, accounting for nearly 10.4%." However, if we also count the children of over 40,000 Vietnamese brides with Korean husbands, the Vietnamese diaspora figure would likely be higher. Finally, we also need to mention the significant Vietnamese communities that were present in some Eastern European countries before the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, primarily due to labor migration agreements between Vietnam and the communist regimes in the region.

Currently, about 570,000 Vietnamese live and work in Japan. Of these, 35% are interns or trainees, according to Asahi Shimbun. Vietnam is at the top of the group of 15 countries sending interns and laborers to Japan. They contribute to maintaining important industries such as construction, agriculture, and healthcare, while Japan's birth rate is increasingly low, and there is a shortage of caregivers for its growing elderly population. However, an increasing number of Vietnamese interns are being arrested in Japan for theft and other crimes, causing concerns in Japan and signaling deeper underlying problems.

In East Germany (German Democratic Republic), tens of thousands of Vietnamese workers were brought in as guest workers through agreements between the two countries starting in the 1970s. They were concentrated mainly in cities such as Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz), Dresden, Erfurt, East Berlin, and Leipzig. After reunification, many lost their jobs and returned to Vietnam or moved to West Germany. A well-known German of Vietnamese origin is Philipp Rösler, who was a Vietnamese orphan and served as Vice Chancellor of Germany. He was born in 1973 in Khánh Hưng, Sóc Trăng, Vietnam, and was adopted by a German couple when he was young. Rösler has overcome many difficulties to become Germany's youngest Vice Chancellor and a highly influential politician in the country. Currently, Philipp Rösler serves as the Chairman of the Advisory Board of VinaCapital Ventures investment fund in Vietnam, specializing in investing in technology and startups. In Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia), there was also a fairly large Vietnamese community who came as workers, estimated at about 60,000 people before 1989, currently over 83,000 people (including those who have acquired local citizenship). Poland had one of the largest Vietnamese communities in the region before 1989; estimated at 20,000 to 40,000 people, Vietnamese came here as students or contract workers under agreements with the communist authorities. Other Eastern Bloc countries such as Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania also hosted smaller communities of Vietnamese workers and students during the Cold War due to similar agreements with Vietnam.

Finally, China should also be mentioned. After April 30, 1975, about 250,000 ethnic Chinese, mostly farmers, fishermen, and artisans, fled to China due to the anti-Chinese pressure from the Vietnamese government. They were settled and worked on state-managed farms in southern China and integrated into local life. Conversely, there is also a community of Vietnamese origin who still speak Vietnamese at home, sing Bắc Ninh quan họ folk songs, and eat fish sauce. They are mainly Kinh people who migrated by sea from Đồ Sơn, Hải Phòng, northern Vietnam to China about 500 years ago. They settled in the Tam Đảo area, belonging to Giang Bình commune, Đông Hưng (Dongxing) town, Guangxi province, more than 25 km from the Móng Cái border gate of Vietnam. There are an estimated 32,000 Kinh people in China, mainly living on three islands: Vạn Vĩ, Sơn Tâm, and Vu Đầu. Gradually, the three islands were silted up to form the current Tam Đảo peninsula. This community still maintains Vietnamese language and culture, including speaking Vietnamese and organizing traditional festivals. They often invite elders from Trà Cổ (Móng Cái City) to guide the organization of festivals and communal house worship. There are four major festival seasons each year, which are occasions for everyone to enjoy and pray for good luck. The Kinh people here are also one of the ethnic groups with rich cultural identity in China, with the support from the government in learning Vietnamese and maintaining cultural traditions. Previously, they were allowed to have two children (instead of one for the Han Chinese) and received extra points for college admission similar to "affirmative action" for certain people of color in the US. (According to Phuong China Vlog).

Note: This is an English adaptation of an original article in Vietnamese: Người Việt Hải Ngoại Sau 50 Năm Phần 1 (1975-2025)

For references, please go to the original article at the following link:

(To be continued)

Hồ Văn Hiền

May 21, 2023

March 7, 2025